Hello. Hope February has been treating you well.

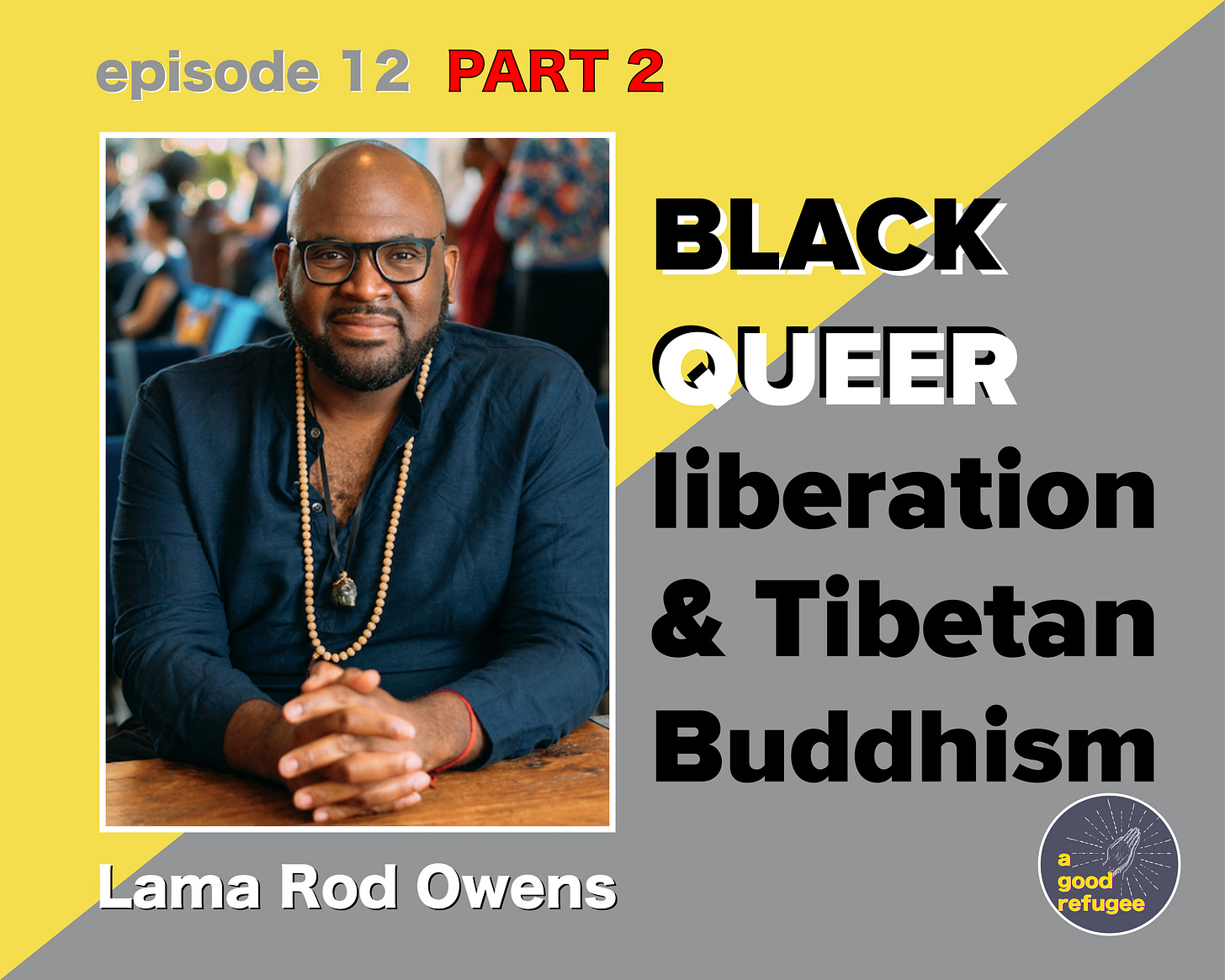

In the second and concluding part of Gelek’s conversation with Lama Row Owens, they speak about the loss of magic and exploring Indigeneity (01:25); holding space for anger and violence in creating justice and peace (09:05); the weaponization of niceness (20:55); bodies, movement and breathing in the time of a pandemic (22:40); and more.

If you missed part one of the conversation, click here.

Episode notes

Loss of magic and exploring Indigeneity. [01:25]

Loving our anger. [03:56]

What Black History Month means to Lama Rod. [06:15]

Holding space for anger and violence in creating justice and peace. [09:05]

Discussing police, prison abolition, political systems and institutions in dharma teachings. [15:29]

Weaponization of niceness. [20:55]

Bodies, movement and breathing in the time of a pandemic. [22:40]

Lama Rod’s current and upcoming projects. [26:30]

Interview transcript

You have a chapter towards the end of [Love and Rage] where you speak about the loss of magic.

Yeah, that’s part of my Indigenous work right now. This is work that I hope to present in the next couple of years—me connecting more to my African as well as Native American ancestry, and putting all of that in conversation with Tibetan Buddhism. For me, again, it’s a synthesis of what’s being created. I think “Love and Rage” was a good beginning step to demonstrate how I am transitioning into this space. As an American Black person, my Indigenous spiritual practice is hoodoo. Hoodoo derives from the practice of Africans coming on to the West, meeting Christianity, and developing the system of philosophy, ritual magic and so forth. It’s so related to tantra and Vajrayana in Tibetan Buddhism. I wanna understand how I can synthesize that even more so that it’s more authentic for me.

I remember years ago, Rinpoche [Norlha] was talking about the magic of Native Americans. He was saying, “Native Americans were so strong that they survived genocide.” It really struck me when he said that. For me, that was just the way he recognized the validity of this community of people. He respected Native American gods and spirits.

When Kundun [HHDL] makes his trip to North America, he always makes it a point to also have representatives or emissaries from the local First Nations or the Native communities to meet with them and speak with them. I always find it beautiful how there are these patterns of elemental rituals that’s consistent across hemispheres, cultures and Indigenous communities. I am reminded of, for instance, the whole myth or idea of how Buddhism was propagated by Padmasambhava [in Tibet], and him having to clash with nagas and deities. It’s very fascinating to actually look into those things, and I’m really excited for this project that you are undertaking.

The title of the book itself, I was curious about that. When you placed “Love and Rage” in that order, was that intentional?

Yeah absolutely. The title came first before the content.

Like not “Rage and Love,” but “Love and Rage.” Was that intentional?

Yes, because love holds the rage. Love leads. So, when I talk about this conversation between love and rage, it’s not a fight. It’s more about how love is holding the space for our rage to be there. Love is the container that holds everything. If there is no container of love then that rage actually becomes an expression of violence.

“My anger is like a living being I am in partnership with.” And then a couple of pages later you say, “Loving our anger invites it into a transformative space where it emerges as the teacher.” That’s so profound. I wonder if you can expand on that a little bit.

That’s rooted within the teachings around the manifestation of the guru. How the guru is manifesting in the phenomenal world. One of those manifestations of the guru is through emotions. Once we pay attention to the emotion, the emotion is actually trying to teach us how to be in relationship with it. For so much of our lives, we tend to be overreacting and running away from our emotional reality. But to turn our attention back to something like anger, we begin to hold space for it and to experience it, that experience begins to teach us about the nature of emotion. And of course the nature of emotion is the nature of the mind itself. Once we realize that, the guru emerges in that moment.

You’re saying anger can be a vessel that helps take us to the ultimate reality.

Well, anything can take us to the ultimate. The nature of the whole phenomenal world is of one essence. So if we recognize the nature of that phenomena—an emotion, an object, an idea, whatever it is—it unlocks the nature of all phenomena, and that opens us right into the ultimate.

Does Black History Month hold significance for you?

That’s a good question. It doesn’t hold significance for me because I feel like I’m always celebrating my history and culture. It’s not relegated to one month—the shortest month of the year, by the way. I just think that we have to establish a culture where we’re celebrating all the parts of our history; all the different groups and communities that have helped shape the world. We should have knowledge and an appreciation of that.

And yes, I understand that there are histories that have been so silenced that we have to create and designate these periods of time to bring attention to it. But I really want to take it to a point where we don’t need to have a special time to think about these things. That it just happens naturally. That we think about Black folks, Asian American communities, queer history, Native American history… where we just know that. And we don’t. There’s so much history that has been erased.

This is different from how some people then take that other approach where they say, “I don’t see race. I’m colour blind.” You’re not saying that at all. You actually have a passage—I can’t find it right now—in your book where you affirm and celebrate the different histories, traditions, lineages that we embody.

Yeah, I see differences. I love that. Again, it goes back to the teachings of the mind. I can hold space for everything and notice everything. And I can look at the ways in which I have fixations on certain things. I can examine that. That fixation may also mean prejudice. It may mean resistance to certain things. I can look at that and hold space for it and allow it to be this immense amount of openness.

We can hold all the difference in the world but the problem is our relationship to that difference. Is that relationship one of opening and acceptance or is it one of restricting and defining and pushing away?

And asserting power.

And asserting power, absolutely. Because we’re fixated on our sense of self and ego, right? But there has to be space for it too.

Spaciousness is another theme that’s quite prevalent in your book. Early on in your book, you say (in speaking of anger): “In activist communities, our relationship to anger is immature, ill-informed and overly romanticized. We manipulate anger as a false sense of energy and inspiration.”

The first image that came to my mind when I read that line is the burning of the 3rd Precinct building of the Minneapolis police department shortly after the killing of George Floyd. For me that was such a powerful, revolutionary emanation of what activism means but also what taking back justice means. Do you think your line and that image are in contradiction?

I think that one of the things—and this is a really subtle, nuanced argument—that I’m always trying to push for, particularly with activists, is knowing what you’re doing, and not just reacting. If you’re gonna burn a building down, know that you’re burning it and know that you’re doing this in order to hopefully trigger freedom, liberation. Not just cause you’re pissed off. I know that’s a very nuanced thing. Our holding space for anger and reacting to anger may actually look like the same action. Often I’m trying to avoid violence, but at the same time, sometimes violence has to be expressed in order to reduce greater forms of violence.

And so I’m not a 100 percent non-violent person. I think violence can be used skillfully to reduce other kinds of violence and harm. So we have to know what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. The use of violence has to be skillful. And of course people push back, but then I use this example of like, if you have a child and someone runs up and grabs your child, are you going to stand there? Are you gonna do whatever you can to get your child back in that moment?

We all have the capacity to express violence. Every being on this planet has been violent in some capacity or another. What I’m arguing for is can we skillfully use that violence to reduce other forms of violence when we need to. Dr. King said, “Riot is the language of the unheard.” I think that’s important for us. And then, when something needs to be destroyed, can we critically say, OK we’re going to do this? Not out of hate and anger, but out of this need to be heard; to disrupt certain systems that are increasing harm and violence for others.

This is perhaps my own Tibetan neurosis surfacing where I feel like non-violence tends to get weaponized, funnily enough, in how we are meant to come to terms with our traumatization and our oppression. It also operates through respectability politics, where the idea is that if you conduct yourself civilly or in a way that’s appropriate, that somehow it elevates your dissent over others. I think it’s very timely or relevant that you quote Dr. King because I’m reminded of his quote where he says, “True peace is not merely the absence of tension. It is the presence of justice.” That piece, again, gets easily paved over when those in power talk about non-violence or of being peaceful but miss the whole context of justice. And I think that in itself is actually a form of violence.

I totally agree. I think in the west, the teachings of non-violence have been so over emphasized because it comes through a culture of dominance. You’re already at the top, you actually have the privilege of being peaceful and practising non-violence because you’re not fighting for basic resources. And that’s what I have to struggle with in white, western Buddhist convert communities. I have to be conscious of what it means to be Black, particularly a Black man in the south right now, because my life can be at any point in danger depending on where I’m at, who I’m talking with, etc. At no point do I not know that I’m Black, and can be killed because I’m Black.

You say, “My anger is the single greatest threat to my life.” I think that’s a very skillful way to demonstrate that it’s not about you being Black that’s the greatest risk for you, but it’s actually anger.

Well, it’s the anger and how my anger creates a mirror for dominant culture. I am angry because I’ve been hurt through systematic oppression. So I’m not angry just because I’m Black. That’s not an aesthetic of Blackness. It comes from systematic woundedness and oppression.

It’s also a very convenient trope for those in power as well to then misconstrue that anger and say, oh just another typical Black person who’s angry. So you’re constantly having to navigate these very discombobulating experiences and then to comport in a way that makes you feel more agreeable. But that’s not actually true to how you experienced whatever you experienced.

Exactly. And that kind of trope is just another way that we are raised, that lived oppression. “Oh you’re just complaining. You haven’t pulled yourself up by your own bootstraps.” This another mythology that white, American individualism has created that further disciplines us and marginalizes us.

Do you try not to bring in present-day politics into your teachings or is that something you let is come and go as it arises?

It’s so funny you mention that. [Norlha] Rinpoche was so political. He would talk about politics in public teachings all the time.

Like American politics?

Oh yeah. In my teaching, I’m much more interested in systems and institutions because I think those lie at the heart of politics in general. For me, particularly in America, it’s not about the two-party system and democracy. There are deeper issues that we actually have to begin to name for ourselves. That’s where I want the teachings to be. It’s not about who’s the president, it’s why they’re the president. What is the system that gives rise to certain people having power and others not? And we can use dharma to do that. Absolutely.

Do you change your tack in any way when you speak about these issues in the context of a dharma teaching, depending on the audience, or do you keep it consistent?

Yeah, it does depend on the audience. It depends on what country I’m in—that’s a huge thing. The age of folks—when I work with teenagers it’s a different energy as opposed to adults. Is it a BIPOC community? Is it mostly a white group? That all determines how I show up. But I think that mostly I show up in spaces where people are pretty much politically aligned with me.

And that’s the trick here. We’re all excited about Trump being out of the White House, but let’s go deeper now. Let’s talk about what it means to be revolutionary and radical, instead of being centrist and liberal. Let’s talk about how dharma is actually pushing us more towards being revolutionary rather than being conservative. It’s about everyone getting free; everyone getting the resources that they need to be well and happy. It’s very socialist. That’s how I talk. That’s the dharma that I use. Let’s talk about what it means for the people that you don’t even like to be free to have the resources that they need.

For me, just over the past couple of years, my awareness and understanding of things like prison and police abolition has been way higher than it used to be. And I think it would be so amazing if the dharma community cohered around that. I feel that prison abolition is an incredibly complex thing that challenges all kinds of different notions about what we mean when it comes to justice, reformation, rehabilitation and forgiveness. I don’t see a lot of that happening in my limited perspective of the dharma community and I’m really glad for people like yourself who are speaking on those things. Have you noticed a change in the tenor of those kinds of discourses?

I think, for the most part, people are much more educated than they were in the past about mass incarceration, for defunding the police. Climate change, interestingly, is a really safe space for people to get progressive in. [laughs] That’s like very neutral.

Greta Thunberg and the Dalai Lama! [laughs]

Oh yeah. American Buddhist communities: environmentalism, yes! But you start talking about mass incarceration…

Wealth redistribution…

Oh my god. That’s when you run into it. Racial justice. It gets sticky because we’re not linking all this together. If you’re about justice for the environment then you have to be about justice for people and the most marginalized. This is why I love this kind of philosophy of liberation theology that we get from progressive Christinanity. God is on the side of the most oppressed. We have to bring some of that knowledge and language into dharma. We have to understand that oppression has to be something we disrupt for everyone.

That is the calling.

That’s the calling. Dharma is about the liberation of people, even when we’re the ones who are doing the oppressing—that dharma will actually have to deal with us. And again, we’re not interested in that. We’re not interested in being held accountable, hauled out, or any of that. Until that starts being a thing, it’s like we’re going to maintain this level of comfort.

You have a piece in your book about niceness, where it’s just about making people feel comfortable but not progressing any further than that.

Yeah, exactly. Somehow niceness is dharmic—that’s what we’re supposed to do—when the fact is it’s just weaponized. That’s the first thing I noticed when I started going to sanghas: everyone’s so nice. Then when you start talking about issues of inclusivity—cause I was the only person of colour in my early sanghas, period—people shut down. Then another kind of nice emerges where it’s like, “You don’t have to think about that, Rod. We’re not a racist sangha.” It’s like the movie “Get Out.” It’s like a Jedi mind trick where I literally had people actually turn the teachings around and say, “Rod, you’re too fixated on identity.”

We’re all Africans is another one I’ve heard.

Right. That sounds great. This is why I’ve survived all of that, I went through it, and now I’m in a different space where I need to commit to creating new communities where we’re not having these one-on-one, intro conversations about race. We need to start living and embodying inclusivity and radicalism in this moment, on this spot. How do we do that? It’s not about having the conversation; it’s about living it and doing it right now.

The final piece I want to touch on is about embodiment: all the different ways that you’ve studied it, how you’ve related to your body and those of others as well, especially in the context of the pandemic that we’re currently situated in. How has your relationship to your body evolved?

For me it’s like a deepening relationship to all the ways my body shows up. Even this past year I’ve noticed how when one aspect of my body is off, it impacts all my other bodies. When my subtle energy body is out of balance I’m physically and emotionally unwell. It’s hard for me to connect to others. Even with my physical body, being static and so stationary for a year I feel the impact of that. I also feel the impact of all the vicarious trauma physically. I know that particularly this year so much of my work is going to have to be about getting back into the body—even my yoga practice I haven’t been really doing. Moving and working energy through the body is going to be incredibly important for all of us. The body is necessary for us to process and metabolize trauma, and movement is a part of that.

And also breathing, which is a key piece throughout your practice. I was thinking about how we’re in a pandemic of a disease that affects the lungs and I wonder if you had any thoughts on that. About people who may have contracted COVID, or know people who did, and how that affects the act of breathing, and can be an incredibly destabilizing thing. Breath, as you’ve enumerated many times in the book, is one of the foundational pieces on how we first process all the different energies, right?

Yeah absolutely. Even in general, I think breath is really tricky for a lot of folks. I’ve had to over the years had to develop ways for people to re-approach the breath. Even now, looking at a pandemic that’s really affecting the lungs, one of the practices that I’ve been working with people is kind of like a tonglen practice—this taking and sending practice. As we’re breathing, imagining that we’re breathing on behalf of so many folks who can’t breathe. That’s gonna direct us deeper into the fear of all of this as well. We have to open our minds to the reality that people are dying because they can’t breathe, not just through the pandemic but through social oppression as well. Breath has been a part of how police have attacked Black folks.

I can’t breathe, a slogan from a few years ago.

Absolutely. All of that. Breath is important. Breath is life. We know that very intimately in the practice. Breath carries life force. So we just want to breathe and add this energy and I guess do emotional labour of acknowledging that we can breathe on behalf of so many people who are struggling to breathe. That way we stop taking our breath for granted.

Thank you. Before we wrap up, can you please give us a quick rundown of the things you’re working on right now and looking ahead to?

I have a bunch of different events coming up through February and through March. All of that information can be found on my website. I’ll be also developing some content for the Calm app over the next few weeks so I’m excited about that. I’m being introduced to the Calm network so if people subscribe to Calm, please check that content out.

Are you also working on a book?

I am working on a book. I am kind of in the process of figuring out what area or topic I want to go with; I have a couple of different ideas. I will say that over the summer we will be introducing a brand new course on grief and using a lot of the practices from Tibetan Buddhism and some practices from my own Indigenous practices as well. Creating something that’s going to help people work through what I call the brokenheartedness of not just this past year but the grief of our lives in a way that hopefully will be really powerful and meaningful.

We’ve lost so much ritual because of the lockdown just around grieving and mourning. I know that in many Black communities and churches, funerals are actually a social thing, with lots of spectacle and pomp. It’s also true in Tibetan communities. We actually have 49 days of people gathering in homes and chanting daily. All of that has not been in play, unless you are actively contravening lockdown measures. I think that also speaks to a very special kind of isolation, especially in the moment of when you’re losing someone. So thank you so much for putting that together. I think it’s extremely timely.

Thank you. I appreciate this.

—

Share this post